|

Published online 2 September 2008 | Nature |

doi:10.1038/news.2008.1073 News Galileo duped by diffraction Telescope pioneer foiled by optical

effect while measuring distance to the stars. |

|

|

When Galileo Galilei used a new invention

called the telescope to watch the heavens, he revolutionized astronomy. But

his estimates of the distances to the stars were thousand of times too short. A scientist has now taken a closer look

at Galileo's seventeenth century results in an attempt to explain why the

estimates were so far off the mark1. Christopher Graney, a physicist at

Jefferson Community College in Louisville, Kentucky, argues in a paper posted

to the preprint server arXiv that Galileo was tricked by a phenomenon that

was only really understood two centuries later — diffraction. Graney says that Galileo was actually

observing the diffraction pattern that the stars created in the telescope,

instead of the stars themselves. Known as an Airy pattern, it arises when

light from a point source such as a star passes through a hole. The pattern

is made of concentric circles, with a bright 'Airy disk' in the middle —

which it seems that Galileo thought was the star. For fainter objects, the edges of the

disk are hard to see, making it look smaller, whereas brighter stars produce

a larger Airy disk. Because Galileo thought that all stars were the same size

and brightness as the Sun, he concluded that the smaller stars he observed

through his telescope were simply further away. So Galileo tried to infer the stars'

relative distance from Earth, in terms of what we now call astronomical units

(AU), by measuring their diameter. One astronomical unit is the distance from

Earth to the Sun, about 150 million kilometres. He deduced that the stars

were hundreds to thousands of AU away. In reality, the nearest stars are

about 300,000 AU away. Duplicitous disk To unravel Galileo's mistake, Graney

calculated the intensity of the diffraction pattern for stars of different

brightnesses. He then worked out Galileo's detection threshold and calculated

the size of the Airy disk that each different star would have produced in

Galileo's telescope. Drawing a graph of the stars' brightness

against the apparent diameter of the Airy disk gave Graney a roughly straight

line that looked very much like Galileo's own data — strong evidence, says

Graney, that the astronomer was indeed being fooled by the Airy disk. Historians have long known that Galileo

was looking at spurious images of the stars. But Graney's work pinpoints

exactly how diffraction could have tricked Galileo, says Noel Swerdlow, a

historian of science at the University of Chicago, Illinois. "Showing

the linear relationship between magnitude and apparent size does explain how

Galileo could believe that," he says. Although Galileo's assumptions about all

stars being identical to the Sun turned out to be wrong, they were reasonable

given the state of scientific knowledge in the seventeenth century, says

Graney. "He would have seen nothing to contradict that point of

view." Parallax view Astronomers now measure the distance to

stars using the parallax technique, in which the apparent location of a

distant star changes slightly as Earth orbits the Sun, allowing a distance to

be deduced from the angle between those locations. This technique was first

used in 1838 by German astronomer Friedrich Bessel. Graney's work shows just how good Galileo

was at taking measurements, says Don Salisbury, a physicist who teaches

history of science courses focusing on Galileo at Austin College, Texas.

"Galileo was indeed able to measure to an accuracy in which the

diffracted image would be measurable," he says. And Galileo's estimates were far larger

than the distances to any astronomical bodies known at the time. "300 AU

is close compared to modern ideas about the stars, but it is more than 10

times further than Neptune, and 30 times further than Saturn, the most

distant planet known in Galileo's day," says Graney. "It's a long

way, and I'm sure it seemed quite far to Galileo and his

contemporaries." ·

References 1.

Graney,

C. M. Preprint at http://arxiv.org/abs/0808.3411 (2008). |

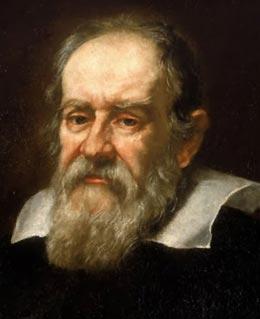

Galileo

Galilei, as painted by Justus Sustermans in 1636. |

http://www.nature.com/news/2008/020908/full/news.2008.1073.html